Books • Interview • Writing • Biographer

The Story of Sicily's Greatest Medieval Queen, Margaret of Navarre, Regent from 1166 until 1171

For five eventful years Margaret – who died in 1183 – was the most powerful woman in Europe and the Mediterranean, governing a polyglot realm of some two million subjects living on Sicily and in peninsular Italy south of Rome in the regions of Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, Molise and Calabria. Born in La Guardia, in Navarre, in 1135, and raised in Pamplona, she wed William I of Sicily in 1149 and eventually succeeded him as regent for their young son, William II.

For five eventful years Margaret – who died in 1183 – was the most powerful woman in Europe and the Mediterranean, governing a polyglot realm of some two million subjects living on Sicily and in peninsular Italy south of Rome in the regions of Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, Molise and Calabria. Born in La Guardia, in Navarre, in 1135, and raised in Pamplona, she wed William I of Sicily in 1149 and eventually succeeded him as regent for their young son, William II.

Her regency is full of details generally overlooked by past historians writing about the Kingdom of Sicily. For example, under Margaret's administration and protection was the largest population of Muslims living within the formal authority of a woman, a malikah who counted Arabs among her trusted courtiers.

Yet Margaret's first biography wasn't published until 2017 even though her biographer, Jacqueline Alio, had contemplated writing the queen's story for some twenty years, ever since attending an academic conference in Palermo in 1994 at which the queens of Sicily were all but ignored. Finally, following research in southern Italy and northern Spain to investigate some lingering yet commonplace misperceptions about this singular queen, effectively correcting a few errors made by earlier historians (the author's comments appear elsewhere), the first biography of Queen Margaret found its way into print.

Margaret reposes in Monreale Cathedral (described at length below), where there is an icon of Thomas Becket rendered in mosaic in the apse.

More is known about Margaret than any other Sicilian queen of the Norman-Swabian era that ended in 1266. Her biography established a new subject category in major libraries, something highly unusual in today's crowded academic environment, and sparked new interest in her among junior scholars.

Here you can download a 144-page preview of the book as a PDF file or read its Preface and Epilogue, which are also included in the preview.

Preview of the Book in PDF: Includes the preface, acknowledgments, table of contents, introduction, chapters 1-Identity, 2-Kingdom, 3-Princess, 4-Betrothal, 6-Motherhood, first pages of other chapters, epilogue, Appendix 5 (Letters), Appendix 6 (The Pendant), Appendix 10 (Margaret's Decrees), first 55 endnotes, index.

Margaret, Queen of Sicily (ISBN 978-0-991588-65-7) is available from Amazon US, Amazon UK, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone's, Indigo, Fish Pond and other book vendors. Exclusive vendors in Sicily: Libreria del Corso, Via Vittorio Emanuele 332 (between the Quattro Canti and Piazza Bologni), Palermo; Museum Bookshop (in the cathedral museum and portico), Monreale Cathedral. It is available as an ebook in an abridged edition (having an abbreviated bibliography, fewer appendices, no endnotes) as Queen Margaret of Sicily (ISBN 978-1-943639-23-6) from various vendors and with Hoopla™ through some libraries. Visit the Librarians' Page for a list of wholesale distributors of this title and others about the queens of Sicily.

Also by Jacqueline Alio

(Described further on the Librarians' Page)

Preface

Extracted from Margaret, Queen of Sicily

© 2016 C. Jacqueline Alio

As Queen Regent of Sicily, Margaret Jiménez of Navarre was the most powerful woman in Europe for five eventful years. She was the most important woman of medieval Sicily. If only for that simple reason, her story is worthy of our interest. But there are other reasons to consider her life and times.

Margaret of Navarre represents the dynastic and social bridge between Sicily and the northeastern Iberian lands. This began with the marriage of Roger II, Sicily's first king, to Elvira of Castile, Margaret's cousin. It was destined to reach a fuller fruition with the marriage of Frederick II to Constance of Aragon in 1209 and, of course, the crowning of Peter III of Aragon as King of Sicily in 1282. Coming on the heels of the bloody War of the Vespers, this last development led to Sicily finding herself in the Iberian political orbit for the next few centuries, first as a jewel in the "Crown of Aragon" ruled from Barcelona, and then as a cornerstone of the Spanish Empire.

Margaret's relationships with Thomas Becket and her Navarrese countryman, the rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, say as much about each of these two men as they do about her and her adopted people, the polyglot Sicilians.

"You have gained praise among your countrymen, and glory among posterity, and made us your debtors," wrote Thomas Becket to Margaret in a letter thanking her for extending hospitality to his family when they were exiled from England by King Henry II, whose daughter ended up marrying Margaret's son.

"You have gained praise among your countrymen, and glory among posterity, and made us your debtors," wrote Thomas Becket to Margaret in a letter thanking her for extending hospitality to his family when they were exiled from England by King Henry II, whose daughter ended up marrying Margaret's son.

Like most past ages, Europe's High Middle Ages were not a great era for women. They were benighted times that witnessed very few females groomed to lead nations, or indeed anything more grandiose than a convent or a kitchen. Yet the first century of Sicily's life as a kingdom saw two intrepid women pilot the realm through perilous waters. Margaret of Navarre, as we shall see, became queen regent; a few decades later, Constance of Hauteville, who inherited the Kingdom of Sicily, was queen regnant. They knew each other, and young Constance may even have patterned part of her "leadership style" after Margaret's. A sisterhood, though tenuous, probably existed.

Both were the daughters of kings, the sisters of kings, the mothers of kings. In youth, neither seemed destined for greatness, or even queenship. It was widowhood that prompted their ascents to power. Their lives deserve to be studied, or at least noted, for there is something to be learned from them. Our focus, of course, is Margaret, who arrived in Sicily at the end of her girlhood. Indeed, it was the arrival itself that brought her girlhood to an end.

Inevitably, Margaret's story, like those of the queens who were her contemporaries, is to some degree defined dialectically by the entrenched patriarchy. In her time there were kingdoms but no true European queendoms. Chroniclers recounted more tales of heroes than heroines.

It is inescapable – a formless subtext lurking in the shadows cast by the long march of centuries. Sooner or later, any biography of a female leader must confront the thorny question of gender. Therein lies a latent sexism, a lingering vestige of the infamous double standard that colors the ages, for nobody writing about a man is expected to address the subject's masculinity as if it were a barrier to be overcome. We need not dwell on this tired topos, nor make it the object of arcane debates, but we cannot ignore it.

Women are different from their brothers, and those differences were far more acute in the twelfth century – an epoch of absolute monarchies, absolute roles and absolute power – than in our time. In practice, the act of ruling was essentially the same regardless of the sex of the ruler; it was the ubiquitous misogynists who created most of the obstacles facing those few queens who found themselves actually governing kingdoms.

During the Middle Ages, Sicily was one of the few places where a woman ruled a population that included many Muslims. Yet the more outspoken men who challenged Margaret's authority were not the kingdom's Muslims, but rather its Christians, including two of her kinsmen.

Anybody familiar with chess, a game introduced in Sicily by the Arabs, knows that the queen is the most versatile piece on the board. She can defend her king or attack opponents. Margaret proved adept at both tactics. Checkmating foes was part of the job.

Medieval queenhood was more grit than glitter. Despite good meals, comfortable beds and occasional pageantry, ruling a kingdom was a burdensome task.

Twelfth-century queens regent and regnant assumed the duties usually reserved to men. Thus we find Constance of France, the widow of Bohemond of Antioch, a monarch of Sicily's House of Hauteville, acting as her son's regent and knighting the boy herself.

The historiography and method that led to this biography are considered at some length in the following pages. For the moment, let it suffice to say that sound epistemology is key, and if our quest for accuracy is essential so is the balanced presentation of history. Historical biography must never wander into the domain of historical fiction.

Margaret's travels took her from her native Navarre to Sicily, a tortuous path followed, very literally, by the author, albeit using slightly more modern means than horse and galley. From Pamplona to Palermo, across seas and mountains, Margaret edged her way to greatness, step by step, out of simple necessity. It was not an easy road, nor even an expected one.

The lessons learned are general, perhaps abstract. Chief among them is the very simple idea that strength springs forth from our response to adversity. This is something embodied not only by "leaders" but by women who face challenges in their daily lives; the single mother and the businesswoman have much in common with Margaret of Navarre.

Because our journey follows Margaret's, we'll cast an eye over the social environment she found in the Kingdom of Sicily, which included the islands of Sicily and Malta, and most of the Italian peninsula south of Rome. The realm, the Regnum Siciliae, boasted a prosperous, multicultural population, a fair degree of independence from the Papacy, a reasonably efficient feudal system of land ownership and, not leastly, a solid legal code, the Assizes of Ariano, inspired by the Code of Justinian. The middle years of the twelfth century found the kingdom with one of the wealthiest economies in Europe and the Mediterranean, having a population distinguished by its ethno-religious and intellectual diversitude.

We shall, of course, glance over the reigns of three kings Margaret knew, the men who shaped her life. These were her father García Ramírez, her father-in-law Roger II, and her husband William I. Then there was the reign of her son, William II, for whom she was regent. However, ours will not be an exhaustive study of those kingly reigns, to which entire volumes have been dedicated. Nor will it focus exclusively on chronicles and charters, although such sources shall be considered extensively.

Island kingdoms seem to enjoy a special niche in history, and certainly in literature. Tragically, one finds few obvious traces of Liliuokalani's noble legacy in Hawaii. More celebrated are the signs that Margaret left in Sicily, among them the magnificent cathedral at Monreale, which her son built and where she rests.

The name Margaret is thought to derive from ancient Persian or Greek words for pearls, clusters of pearls, or blossoms. Saint Margaret of Antioch was a Christian virgin martyred in 304. Queen Margaret's death at forty-eight years was a natural one, though far too premature.

This book is not an encomium. In life, Queen Margaret was loved and despised, praised and disparaged. Such is the fate of queens. Among sage historians her detractors are few, her legacy assured. But nobody has ever seen fit to write a book about her, until now.

The story of Europe's eventful twelfth century is now one step closer to completeness. Fortitude, thy name is woman.

Epilogue

Extracted from Margaret, Queen of Sicily

© 2016 C. Jacqueline Alio

The memory of their Spanish queen did not soon fade from the Sicilians' memory, but their attention turned to focus on the king's wife. Virtually nothing is known about Joanna's time as queen consort, except that she bore no children. In the spring of 1184, she went with William to Calabria to comfort its population following a destructive earthquake powerful enough to force the collapse of Cosenza's cathedral.

The traveler bin Jubayr arrived in Sicily too belatedly to meet Margaret, but he left us a perceptive description of what he found.

A year after Margaret's death, William arranged the marriage of his aunt, Constance, to Henry, a son of Frederick Barbarossa. This may have reinforced Sicily's bonds with Germany, but any child of Constance would be a Hohenstaufen, not a Hauteville. The queen dowager Beatrice of Rethel, Constance's mother, died a few months after the betrothal.

In 1185, while Constance was making her way northward to marry Henry Hohenstaufen, William launched an invasion of the Greek lands to the east of the Regnum, something he had been considering ever since the Byzantine massacre of the Latins at Constantinople a few years earlier. Leading this incursion was Tancred of Lecce and an able admiral named Margaritus of Brindisi. The Sicilian advance toward Constantinople was stopped by Emperor Isaac Angelus Comnenus, with whom the King of Sicily made peace four years later.

When Saladin captured Jerusalem late in 1187, the only military opposition to arrive from Europe was the Sicilian fleet led by admiral Margaritus. The next year, Margaritus of Brindisi relieved the Knights Hospitaller, who were besieged by Saladin at their large fortress, Krak des Chevaliers.

With other Christian kings, William was already contemplating a Third Crusade to take back the Holy City.

When King William II of Sicily died in November 1189, his aunt Constance was his designated heir. The Sicilians, not wishing to see the Regnum fall into the hands of the Holy Roman Emperor, crowned illegitimate Tancred of Lecce their king. Initially, there was nothing Constance could do about this.

Henry II of England died in the same year, succeeded as king by his son Richard Lionheart.

In 1190, Constance's father-in-law, Frederick Barbarossa, met his end while riding across a river in what is now Turkey. His son, Constance's husband Henry VI, was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome the following year.

Queen Joanna, Margaret's daughter-in-law, survived William and in 1191 she went on the Third Crusade with her brother, Richard Lionheart, who tried to marry her off to Saladin' brother as a peace offering. Returning to Europe, she wed Raymond VI of Toulouse as his third wife. (Joanna died following childbirth in 1199.)

Thinking to overthrow Tancred, Constance and her husband invaded the Regnum. This incursion ended with Constance being captured. She was rescued in 1192.

With Tancred's untimely death in 1194, Constance again claimed the Kingdom of Sicily as its lawful queen regnant. This time she was successful. By her husband, Henry VI, she bore a son, Frederick II. This ushered in Sicily's Swabian era. Frederick was Holy Roman Emperor, King of the Germans, King of Sicily, and eventually King of Jerusalem. Following in the intellectual tradition of his grandfather, Roger II, erudite Frederick led Sicily into a second golden age.

Margaret’s brother, Sancho VI "the Wise" of Navarre, died at Pamplona in 1194. His daughter, named Berengaria (like the daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile), had wed Richard Lionheart in 1191, thus becoming Queen of England and daughter-in-law of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Berengaria’s marriage to Richard was childless.

Margaret's nephew, Alfonso VIII of Castile, is celebrated for his part in Spain's Reconquista. He defeated an Almohad force at the Battle of the Navas de Tolosa in 1212, but died two years later.

Looking back across many generations, we can see that the people who touched Margaret's life were the most colourful figures of their era. The patina of the passing centuries has not lessened their legacy, nor has it tarnished hers.

The story of Margaret Jiménez of Navarre is the story of every woman who rises to face the unknown and defeats it. Her story is our story.

Monreale Guide

© 2017 C. Jacqueline Alio

From Norman-Arab-Byzantine Palermo, Monreale and Cefalù

One of the peaks overlooking the Genoard park to the immediate south of Palermo has come to be called Mount Caputo. Except perhaps for a tiny Arab village, the mountain seems to have been uninhabited until 1172. Favored for its hunting, it afforded the visitor a commanding view of the city. The site was known for its springs.

Queen Margaret, the mother of King William II, loved such places so much that she was already undertaking the construction of an abbey near Maniace in the Nebrodian Mountains on the site of a dilapidated Greek monastery. It didn't take much to convince William to pursue a similar project near the capital, where he and his mother could oversee the details.

With royal involvement, the place was renamed, appropriately enough, Mons Regalis, "Royal Mountain." It is now called Monreale. Mother and son planned to erect Sicily’s most beautiful church on this spot, along with the island’s largest monastery and a walled town. A castle would be built on the rocky summit overlooking the church. (The idea that an earlier, Greek Orthodox, church once stood on the Monreale site is based on the mistranslation of a medieval record.)

The planning of such a project could not be kept secret for very long. Walter, the zealous Archbishop of Palermo, the highest-ranking prelate in the Kingdom of Sicily, was chagrined to hear about it. He wanted funding for his own enterprise, an expansion of Palermo’s cathedral.

Historians generally agree that, whatever moved William to begin his venture at Monreale, one of the reasons was to make a public gesture of his independence from Walter, who was his former tutor. In a time when tangible symbols were the most salient, Monreale was a royal reproach, a sign that Walter's power was on the wane.

Writing long afterward, the chronicler Richard of San Germano believed that the construction of the abbey church at Monreale was suggested to the king by Matthew of Aiello, the royal vice chancellor. He tells us that Matthew despised Walter, and vice versa, yet the two men behaved amicably toward each other in public. He goes on to report that Monreale reflected a certain diminution of Walter's effective power.

Yet Peter of Blois, who, like Walter, was once the king's tutor, seems to have surmised William's intention to assert himself upon reaching the age of majority. This the young monarch did by interrupting his formal studies as soon as he could.

Peter later exploited this fact to compare William II of Sicily unfavorably to a much older Henry II of England, who eventually became the Sicilian king's father-in-law: "Although your king has studied well, ours is far more learned. In fact, I have had the chance to assess the practical education of both monarchs. As you know, the King of Sicily was my pupil for a year, having already studied with you to acquire a knowledge of general studies and literature. He was able to benefit from my special efforts to motivate him, but as soon as I departed from the kingdom he fell into the habit of reading frivolous books and enjoying royal pleasures."

There may be some truth in this. Few sovereigns were as erudite as Henry of England.

Although the King of Sicily and his guests could stay at the castle above Monreale, there would also be a comfortable palace on the north side of the church's apse (what remains of this edifice is now the city hall). From the highest floor of the palace, the royal family could see Palermo, just a short ride away, yet enjoy the privilege of being, quite literally, above the petty intrigues that infested the court in the city far below. Queen Margaret appreciated this, and so did William, who had been raised amidst a succession of troublesome plots.

From the outset, Monreale Abbey, officially "New Saint Mary's," was intended to be part of a vast monastic complex of the Benedictines, far larger than Saint John of the Hermits near the royal palace in Palermo. The monks of Cava, near Salerno, were happy to oblige the king by sending some of their number to Monreale.

By longstanding tradition, major Benedictine abbeys like Cassino and Cava were autonomous, answering, through their order's hierarchy, to the Pope himself. Local diocesan bishops had little say in monastic administration. Pope Alexander granted Monreale's Benedictines a similar privilege. This meant that they were outside Walter's jurisdiction. All he could do was watch as the new church took shape.

King William endowed the monastery with extensive lands and towns populated largely by Arabs: Corleone, Jato, Partinico, Battallario, Calatrasi. The Arabs' villages bore names like Rahal Algalid and Menzil Zarsun. This was a vast, fertile territory bordering the Archdiocese of Palermo. No wonder Walter was distressed.

With Papal and royal approval, the abbot of Monreale gradually obtained authority over numerous monastic estates in Sicily, such as those founded around Maniace, and some in regions as far afield as Apulia.

The construction of the town, the hilltop castle, the royal palace and the walls encircling the abbey seems to have begun in 1172, but one or two years were to pass before work commenced on the church and monastery following Papal approval for the project.

The greater part of the church's Romanesque superstructure was completed by 1180, and two years later Pope Lucius III made it a metropolitan cathedral, its abbot obtaining the rank of bishop. It would be another few years before the mosaics in the church and the columns in the cloister were completed.

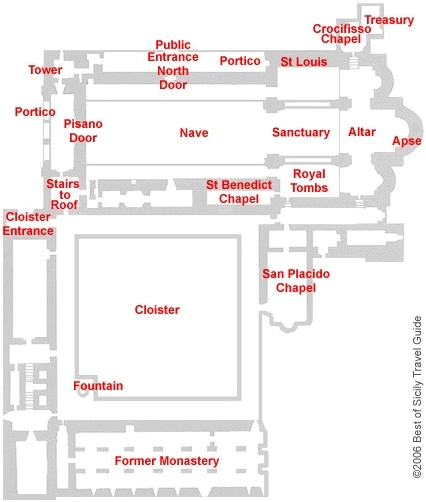

Building such a monument required a monumental effort (maps follow the text).

The Church

Whether one refers to it as a basilica, duomo or cathedral, the church around which Monreale was built is impressive. The layout is a classic cross plan with a transept. The two massive towers were meant to serve as fortifications. The floor area measures slightly over four thousand square meters (more than forty thousand square feet), the nave being just over a hundred meters (at three hundred thirty feet) in length. The nave is positioned generally, but not precisely, on an east-west axis ad orientem, with the apse toward the east, toward Jerusalem. This tradition dates from the early centuries of Christianity in Greece and elsewhere in Europe. In former times, the celebrant faced the altar and apse during liturgy; this is still true in the Orthodox Church, and it was the case in the Catholic Church until the twentieth century, when altars were positioned so that the priest faced the congregants.

There was initially a Byzantine templon, essentially a low iconostasis (icon screen), separating the sanctuary from the nave.

Inside the church is a wide central aisle between two narrower ones, for a total nave width of forty meters. Eighteen monolithic columns support the arches. These pillars were not built for the church; they were taken from a temple in Rome, and many of their capitals bear the likeness of Roma, one of that city's deities. Most of the Corinthian columns are made of syenite, an igneous rock very similar to granite but bereft of more than rare traces of quartz. It takes its name from Syene (Aswan) on the Nile, where the Romans quarried it.

The church's wooden roof replaces the one destroyed by fire in 1811. The original ceiling had muqarnas "stalactites" similar to those of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo.

An interesting detail is the occasional use of strata of timber between some of the large stones of which the thick walls are constructed; this serves as a soft buffer to absorb seismic shock that creates fissures during earthquakes. Among the distinctively Arab features are the geometric motifs of the exterior of the three apses.

The Mosaics

What most strikes the visitor are the walls covered with mosaics set upon an endless field of gold tesserae. At six thousand three hundred and forty square meters (nearly seventy thousand square feet), thus eclipsing the wall area of the mosaics of Saint Mark's in Venice by around thirty percent, this is the largest medieval display of its kind in western Europe. It was inspired by the mosaics of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo. Compared to the chapel, however, one is struck by the sheer scale of Monreale.

Many figures are icons, while others are Biblical scenes. The Old Testament is depicted on the walls of the central aisle. The mosaics of the lateral aisles and those above the sanctuary depict the New Testament. Many are accompanied by inscriptions in Latin or Greek. All the saints but one are venerated in the Orthodox Church. The lone exception is Thomas Becket, depicted in the central apse; this is the earliest public image of Saint Thomas of Canterbury.

Overlooking the royal thrones in the presbytery, one mosaic shows King William II offering the church to the Virgin Mary, while another shows the same king being crowned by Christ, recalling the mosaic in the Martorana Church depicting Roger II receiving the crown from Jesus. The two quasi-heraldic lions passant guardant facing each other in the triangular mosaic immediately above the royal throne on the north wall resemble the heraldic beasts in the royal coat of arms of England (displayed by English kings beginning with Richard Lionheart) and the lions flanking the royal throne dais in the Palatine Chapel in Palermo's Norman Palace, repeated in a motif of the exterior of the apse of that city's cathedral.

Dominating everything is the imposing icon of Christ Pantocrator, "Ruler of All," looking down from a half-dome high in the central apse above the main altar. At thirteen meters wide and seven meters high, this is thought to be the largest medieval image of the Pantocrator to survive. Indeed, the extent of Monreale's mosaics dwarfs that of any similar display that survives from the Middle Ages in what was once the Byzantine world. Beneath the Pantocrator is the Theotokos, the Mother of God; below this is a window of fine Fatimid design.

Begun by 1180, the mosaic work took nearly a decade to complete.

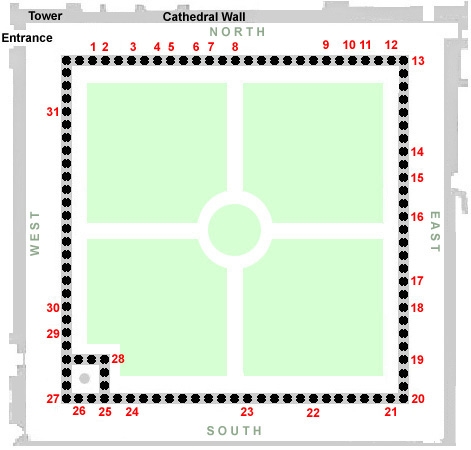

The Cloister

If Monreale's mosaics leave an impression, so does its large cloister. The colonnade is formed of two hundred twenty-eight pillars, most in pairs.

The Fatimid fountain in one corner is very similar to the one in Palazzo Falson in Mdina, Malta. The water spouts from the faces of men and lions carved in relief into a sphere set upon a column of zigzag motifs. When the water spurts out, the fountain's ensemble gives the appearance of a palm tree, representing life. The fountain was probably intended to be placed in the center of the cloister in representation of the spring of eternal life in the garden of Paradise of all three Abrahamic faiths.

Most of the cloister and its decoration are essentially Provençal in style, and it is from that region that its chief sculptors were recruited. Some of the same artisans carved similar capitals at Maniace and elsewhere.

Into the columns' capitals are carved all kinds of Biblical, mythological and natural scenes and personages. There are archers, lions, mermen, boars, and Norman knights bearing long shields devoid of heraldic devices. The Arab warriors are depicted holding round shields. Also present are owls with monks' heads representing vigilance. There are grapes representing autumn and even the depiction of blowing leaves. One scene shows lions devouring men and stags. The double-tailed mermaid sitting among the evangelists and their symbols is Melusina, whose legend was popular in northern Europe. Along the eastern colonnade is a capital showing William II offering the cathedral to the Blessed Virgin Mary and Infant Jesus.

The columns themselves vary in design superficially. Some bear sculpted motifs while others are decorated in patterns with mosaic tiles. The alternating pairing of smooth and decorated columns was meant to create a subliminal sense of endless movement linked to the infinity of God or Allah.

Bordering the cloister is a refectory and dormitory. Beyond these is a large courtyard, the belvedere, from which the entire Gulf of Palermo is visible. The dormitory has been converted into a museum to exhibit artefacts that once belonged to the abbey.

The Royal Tombs

Queen Margaret and two of her sons, Roger and Henry, whose remains were transferred from the Mary Magdalene church in Palermo, rest in the north semitransept. In the opposite (south) semitransept are the two Williams.

A curious detail is the altar near Margaret's tomb dedicated to King Louis IX of France, who died crusading in Tunisia. A reliquary preserves his heart and viscera, placed here during a solemn ceremony in 1270 by his brother, Charles, who was then King of Sicily.

Bronze Doors

Two impressive sets of bronze double doors bearing panels depicting Biblical scenes grace the church. Forged in 1186, the doors beneath the main portico at the end of the nave are by Bonanno of Pisa, who designed his city's leaning tower. The pair of Byzantine design under the north portico is the work of Barisano of Trani. Similar bronze doors designed by both sculptors are conserved in churches elsewhere in Italy.

What one finds at Monreale transcends any single work of art. Here Margaret and her son, William II, fashioned part of the Kingdom of Sicily into a piece of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Castellaccio

About five kilometers north of Monreale on the steep, winding Via San Martino is the sturdy Castellaccio castle, perched atop Mount Caputo, over seven hundred metres above sea level. The fortress originally dedicated to Saint Benedict is visible from some distance away, even from the Porta Felice gate down Via Vittorio Emanuele (a continuation of Corso Calatafimi) by the coast in Palermo.

Its strategic position was intended to guard all the possible approaches to the city, either by land or by sea. This castle is one of a handful of medieval fortresses left standing in the immediate Palermo area. The fortress, which for centuries was used as a monastery, provides one of the most spectacular views of the area. It is well preserved owing to its rather remote location. The ride from Monreale takes about fifteen minutes, and once you park on the side of the road (or in the small parking lot) you have to take a fairly demanding hike up a winding path along the side of the mountain to reach the castle. This hike is never advised for any but the stout-hearted. The castle itself is sometimes open during the high tourist season, with tours arranged by the local mountaineering club. It can be visited when it's closed, if you want to see the exterior and view the magnificent panorama. It's also a good place to have a picnic or simply to enjoy nature.

Cathedral Floorplan

Some Cloister Capitals

1) Arab archer and swordsman, 2) Lions and other beasts, 3) Merman (triton) and standing Norman knights, 4) Parable of Lazarus, 5) Knight attacking beast, Arabs with round shields decorated with lions, 6) Leaves blowing around capital, 7) Naked men killing beasts, 8) Life of John the Baptist, 9) Story of Samson, 10) Mounted and standing Norman knights, 11) Massacre of the Innocents, 12) Evangelists and mermaids, 13) The magi visit Jesus, Annunciation, other events, 14) Men supporting capitals 15) Owls with monks' heads (harpies) and owls as signs of monastic vigilance, 16) Men supporting capitals between beasts and lizards, 17) Story of Joseph of the Old Testament, 18) Abraham sacrifices Isaac, 19) Resurrection of Jesus, 20) Constantine and Helen with True Cross (or William II and Margaret between episcopal cross representing Apostolic Legateship of Kings of Sicily, 21) Lions devouring men and stags, 22) Acrobats, 23) Eagles supporting capital, 24) Arab (wearing turban) killing sheep or goat, 25) Mounted Norman knights, 26) Harvesting of grapes, 27) Apostles, flight into Egypt, cherubs, 28) Wine barrels representing Autumn, on column are signs of Zodiac and symbols of seasons. 29) Old Testament prophets and angels, 30) King William II offers Monreale cathedral to Virgin Mary, 31) Lion slaughters pig as Norman knight and Arab warrior watch

Some Mosaics

![]()

1) Christ Pantocrator, 2) God creates Heaven & Earth, 3) God divides light from dark, 4) God divides waters, 5) God separates land from seas, 6) Creation of sun, moon, stars, 7) God creates birds & fish, 8) God creates Adam and land animals, 9) God rests, 10) God places Adam in Garden of Eden, 11) Adam alone in Eden, 12) God creates Eve, 13) Eve presented to Adam, 14) Eve tempted by serpent, 15) Adam & Eve eat forbidden fruit, 16) God confronts Adam & Eve, 17) Expulsion from Eden, 18) Adam & Eve toiling, 19) Sacrifice of Cain & Abel, 20) Cain kills Abel, 21) God confronts Cain, 22) Cain killed by Lamech, 23) Noah commanded to build ark, 24) Miracle of loaves & fishes (also number 38), 25) Healing of crooked woman (see also number 39), 26) Events from the life, death & Resurrection of Jesus, 27) Events & miracles from the life of Jesus,

A) Noah constructs ark, B) Animals board Noah's ark, C) Dove arrives, D) Animals exit ark, E) Rainbow signifies God's covenant, F) Drunken Noah in vineyard, G) Tower of Babel built, H) Abraham meets angels at Sodom, I) Abraham's hospitality, J) Lot protects angels, K) Lot flees destruction of Sodom with family, L) God commands Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, M) Angel stops sacrifice, N) Rebecca offers water to Abraham's servant, O) Rebecca journeys to meet Isaac, P) Isaac with sons Esau & Jacob, Q) Isaac blesses Jacob, R) Jacob flees Esau, S) Jacob dreams of ladder, T) Jacob wrestles with angel, U) Theotokos & Jesus enthroned surrounded by angels and apostles, V) St Sylvester, W) St Thomas Becket, X) St Paul enthroned, Y) St Peter enthroned, Z) Theotokos & Baby Jesus.

28) William crowned by Christ, 29) William dedicates church to Mary, 30) Healing of possessed woman, 31) Healing of leper, 32) Healing of lame man, 33) St Peter rescued from water, 34) Raising of widow's son, 35) Healing of woman's hemorrhage, 36) Rising of Jairus' daughter, 37) Healing of Peter's mother-in-law, 38) Multiplication of loaves & fishes, 39) Healing of crooked woman, 40) Healing of man suffering edema, 41 Healing of ten lepers, 42) Healing of two blind men, 43) Money changers expelled from temple, 44) Jesus with adulteress, 45) Healing of paralyzed man, 46) Healing of lame & blind, 47) Mary Magdalen washes Jesus' feet.

© 2020 Trinacria Editions LLC, New York